From Beth Elliott,

Author and musician/songwriter.

I absolutely agree that the A La Recherché D’Adam on the first page (205 x 132 cm, to the left of your comment, “It is doubtful that this picture could have been done by a man”) is something powerful that I agree is unlikely to have been done by a man. There’s something very blood-like to me in the red, neither menstrual nor specifically the result of violence (though it could be), that is very matter-of-fact in a “blood and the peeling back of layers of the body happen, this is life, this is natural” kind of way. I can’t quite articulate it, but somehow it speaks to me of a woman’s unflinching awareness of all of the business of blood. Blood, but life continues.

I absolutely agree that the A La Recherché D’Adam on the first page (205 x 132 cm, to the left of your comment, “It is doubtful that this picture could have been done by a man”) is something powerful that I agree is unlikely to have been done by a man. There’s something very blood-like to me in the red, neither menstrual nor specifically the result of violence (though it could be), that is very matter-of-fact in a “blood and the peeling back of layers of the body happen, this is life, this is natural” kind of way. I can’t quite articulate it, but somehow it speaks to me of a woman’s unflinching awareness of all of the business of blood. Blood, but life continues.

I don’t know that “brutal” is the word; some of her pieces strike me as being very chthonic, with the raw power of roots and rootedness, roots that support very large living structures that insist upon people getting out of their way. The structured piece at the bottom of the first page, the  one of the three there without openings, is just such a piece. I don’t think it’s the same one as the one behind her in the first photo on the page, but it has the same kind of power. I have no idea what Mr. Gimpel meant when he said “I don’t like all this in front but I like the background.” I look at the photo, and I see Marcelle looking like a lioness who’s just made good work of a meaty critter and whose expression is “What? That was just eating lunch.” It’s a powerful piece, indeed, and yet it seems it’s just her expressing herself, without making any statement about the power she can put into a work.

one of the three there without openings, is just such a piece. I don’t think it’s the same one as the one behind her in the first photo on the page, but it has the same kind of power. I have no idea what Mr. Gimpel meant when he said “I don’t like all this in front but I like the background.” I look at the photo, and I see Marcelle looking like a lioness who’s just made good work of a meaty critter and whose expression is “What? That was just eating lunch.” It’s a powerful piece, indeed, and yet it seems it’s just her expressing herself, without making any statement about the power she can put into a work.

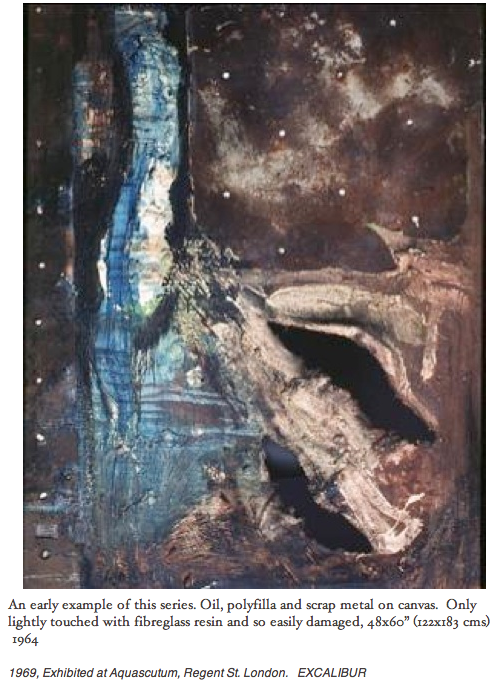

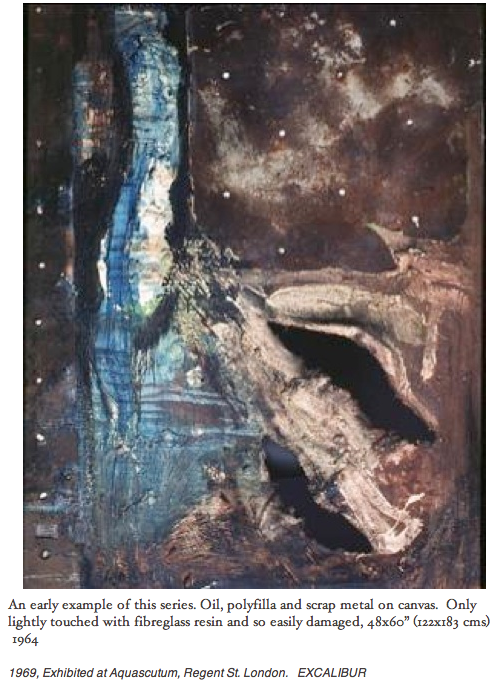

Her work is strong, and yet the brown and blue 1964 piece exhibited at Aquascutum in 1969 is like an ethereal maiden swinging on the crescent moon. Still, her posture, while not in exactly the same angle, is reminiscent of that “roots”-like piece at the bottom of the page. Perhaps there’s a power in both with no need to announce its power, and perhaps that’s what upsets some viewers. And yet, I think that’s very much a woman’s use of power. No talk, just creation.

Her work is strong, and yet the brown and blue 1964 piece exhibited at Aquascutum in 1969 is like an ethereal maiden swinging on the crescent moon. Still, her posture, while not in exactly the same angle, is reminiscent of that “roots”-like piece at the bottom of the page. Perhaps there’s a power in both with no need to announce its power, and perhaps that’s what upsets some viewers. And yet, I think that’s very much a woman’s use of power. No talk, just creation.

The holes seem just right to me, too. I don’t see them as making a statement, which is something I’d expect from a male artist or a woman trying to show she can do non-“dainty” work with the “big boys.” It seems to me Marcelle’s vision was not going to be bound by the stretchers, but she wasn’t in a battle with them. I get the sense she just made her art, and part of her vision was dimensionality. Rather than violence or brutality, I just see strength making a canvas something more than what it is. She determines the physicality of the space for her art. Again, because it’s art, and not a statement that the artist is making art and thereby asserting self/ego, I think it’s very much a woman’s way of being powerful. She wrote that there was a part of herself her pictures.

Marcelle also wrote that she did not see her pictures as brutal but as victims. The holes she opens in her surfaces can be seen as wounds, in a positive way. They are wounds that instead of killing, damaging or weakening her surfaces, allow more inspiration and intuited content to emerge. A key Western archetype relating to wounds and wounding is, of course, the Grail legend of the king with the wound that will not heal. Until the question of what this is and what it means is answered, the kingdom is a wasteland. An alternative take on this comes from viewing the Grail as menstrual imagery (per Shuttle and Redgrave’s “The Wise Wound,” happily back in print), in which the wound that will not heal also will not kill, but rather convey wisdom from the individual subconscious and collective unconscious. Either take is very powerful, and this may explain some of the very visceral reactions to van Callie’s work, both positive and negative.

Bu not only do wounds appear, her surfaces build up, as though the constant destructive-creative forces of Nature are at work. In nature, as in van Callie’s works, this is a relentless and powerful process of change and transformation that proceeds without regard for the human gaze. Van Callie destroys the two-dimensionality of her surfaces, and in that process unleashes a powerful creative force that builds up texture on her surfaces. No wonder some find her three-dimensional work disturbing. That men and women might have very divergent reactions to her work is quite understandable.

![]() And to explore this exciting performance, see

And to explore this exciting performance, see ![]() http://explorethearch.com/index.php Just click on the little ‘Marcelle’ window and follow through.

http://explorethearch.com/index.php Just click on the little ‘Marcelle’ window and follow through.

I absolutely agree that the A La Recherché D’Adam on the first page (205 x 132 cm, to the left of your comment, “It is doubtful that this picture could have been done by a man”) is something powerful that I agree is unlikely to have been done by a man. There’s something very blood-like to me in the red, neither menstrual nor specifically the result of violence (though it could be), that is very matter-of-fact in a “blood and the peeling back of layers of the body happen, this is life, this is natural” kind of way. I can’t quite articulate it, but somehow it speaks to me of a woman’s unflinching awareness of all of the business of blood. Blood, but life continues.

I absolutely agree that the A La Recherché D’Adam on the first page (205 x 132 cm, to the left of your comment, “It is doubtful that this picture could have been done by a man”) is something powerful that I agree is unlikely to have been done by a man. There’s something very blood-like to me in the red, neither menstrual nor specifically the result of violence (though it could be), that is very matter-of-fact in a “blood and the peeling back of layers of the body happen, this is life, this is natural” kind of way. I can’t quite articulate it, but somehow it speaks to me of a woman’s unflinching awareness of all of the business of blood. Blood, but life continues.